The Eighth Amendment Frontier: When a Legal Adult Has the Mind of a Child

The Eighth Amendment Frontier: When a Legal Adult Has the Mind of a Child

The sentencing of a juvenile to life without parole (LWOP) is widely regarded as one of the most profound moral and legal challenges in the American justice system. Grounded in a series of landmark Supreme Court rulings, the principle is now clear: for individuals under the age of 18, such a sentence is unconstitutional, reserved only for the "rare juvenile offender whose crime reflects irreparable corruption." But what happens when a defendant is a legal adult in the eyes of the law, yet possesses the neurological and psychological profile of a child? This is the complex Eighth Amendment frontier at the heart of a case like Mee’s, where the rigid line of adulthood is challenged by the nuanced science of brain development.

The Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on juvenile sentencing is built on a foundation of scientific and social understanding. In Roper v. Simmons (2005), the Court abolished the juvenile death penalty, recognizing that under-18 offenders are inherently less culpable due to their immaturity, impulsivity, and susceptibility to peer pressure. This reasoning was expanded in Graham v. Florida (2010), which prohibited LWOP for juveniles convicted of non-homicide offenses, emphasizing their "greater capacity for change." The capstone was Miller v. Alabama (2012), which banned mandatory LWOP sentences for all juveniles, requiring courts to consider the individual’s age and life circumstances before imposing the harshest penalty.

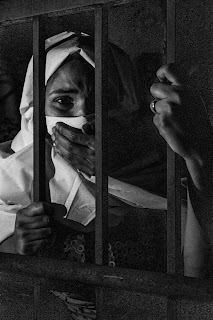

Mee’s case tests the boundaries of this legal precedent. At 19 years old, she was technically a legal adult when the crime occurred. However, her defense team presented compelling evidence of significant mental health and neurological challenges, arguing that her functional age—her decision-making capacity, impulse control, and understanding of consequences—was that of a person far younger. She was not the direct shooter in the murder, a fact that further compounds questions of her culpability. The argument for an Eighth Amendment violation is that sentencing such an individual to die in prison violates the "evolving standards of decency" that the Constitution requires.

The core of the argument is that the logic of Roper, Graham, and Miller should extend beyond an arbitrary chronological boundary. If the Constitution forbids LWOP for a 17-year-and-364-day-old because their brain is not fully developed, does it suddenly become "cruel and unusual" to impose it on an 18-year-old? Or a 19-year-old like Mee, whose documented deficits place her cognitive and emotional age squarely in the juvenile range? To ignore this reality, advocates contend, is to ignore the very principles of lessened culpability and capacity for rehabilitation that underpin the Supreme Court’s reasoning. It creates a situation where a sentence deemed unconstitutional for one person becomes permissible for another, not based on a meaningful difference in brain development, but on a calendar.

The counterargument, however, rests on the necessity of a clear, objective legal standard. The state would argue that the law must have bright lines, and the age of 18 is that line—a demarcation of legal adulthood recognized across countless statutes. The Supreme Court’s rulings were explicitly and intentionally limited to defendants under 18. To extend them, the argument goes, is not for the courts but for the legislatures. While Mee’s circumstances may be sympathetic, her sentence was legally permissible. Allowing individual judges to make case-by-case determinations of "psychological age" would, from this perspective, create judicial chaos and undermine the consistency the legal system requires.

Mee’s case ultimately highlights a growing tension between the law’s need for certainty and science’s revelation of continuum. The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment is not static; it evolves as our understanding of human nature deepens. As neuroscience continues to demonstrate that brain development, particularly in individuals with trauma or disabilities, does not magically conclude on an 18th birthday, the legal system faces a pressing question. Will it cling to the stark division between juvenile and adult, or will it begin to acknowledge that the core principles of justice and redemption must sometimes look past a birth certificate to see the person standing before the court? The resolution of this question will define the next chapter of Eighth Amendment law.

Change Florida’s Unfair Murder Law

Right now in Florida, the law says that everyone involved in a robbery where someone dies is automatically guilty of murder – even if they never touched a weapon, never intended to harm anyone, and had no part in the killing.

This outdated law means people can spend the rest of their lives in prison for actions they didn’t commit. It’s time for change. The responsibility for a death should fall on the person who pulled the trigger, not on anyone who happened to be there.

By signing this petition, you’re standing up for fairness, justice, and common sense. Together, we can call on the Governor of Florida to change this law so that people are judged by their own actions – not by someone else’s crime.

Add your name now and help end this injustice.

Comments

Post a Comment