The Foundation - Is Your Sentence Actually "Cruel and Unusual"?

The Foundation - Is Your Sentence Actually "Cruel and Unusual"?

The Eighth Amendment prohibits "cruel and unusual punishments." For centuries, this was interpreted to ban only certain methods of punishment (e.g., torture, drawing and quartering). However, in the 20th century, the Supreme Court began to interpret it more dynamically, ruling that the amendment "must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society" (Trop v. Dulles, 1958).

Today, a punishment can be "cruel and unusual" in two primary ways:

The What: The Punishment Itself: The nature of the punishment is forbidden for a specific class of offenders or crimes.

Example: The death penalty for a person who committed a non-homicide crime (Kennedy v. Louisiana).

Example: The death penalty for an individual with intellectual disability (Atkins v. Virginia) or a juvenile (Roper v. Simmons).

The How: The Sentencing Process: The way the sentence was handed down violates fundamental fairness.

Example: A mandatory sentencing scheme that prevents a judge or jury from considering the defendant's unique characteristics, such as their youth and its attendant circumstances (Miller v. Alabama).

Your question, "Is your sentence actually cruel and unusual?" hinges on whether your situation falls into one of these categories based on the current state of the law.

The Evolution of the Eighth Amendment: From Dungeons to Courtrooms

The journey has been from focusing on the physical conditions of punishment to the legal and procedural fairness of the sentence itself.

The Early View: "Cruel and unusual" meant barbaric methods of execution or physically horrific prison conditions.

The Proportionality Principle (1980s): The Court established that a punishment must be proportional to the crime. A sentence of life without parole for stealing a small amount of money could be unconstitutional (Solem v. Helm).

The Categorical Bans (2000s-Present): This is the most significant modern evolution. The Court began to identify categories of offenders (e.g., juveniles, intellectually disabled) and categories of crimes for which the most severe punishments are inherently disproportionate and therefore unconstitutional.

Key Supreme Court Cases That Changed Everything

Your listed cases form a critical trilogy in the law regarding juveniles sentenced to Life Without Parole (LWOP).

1. Miller v. Alabama (2012) - The Landmark Ban on Mandatory LWOP for Juveniles

The Issue: Whether sentencing a 14-year-old convicted of homicide to a mandatory sentence of life without parole violates the Eighth Amendment.

The Holding: Yes. The Court did not ban JLWOP outright, but it banned mandatory JLWOP sentences. The ruling requires that before imposing JLWOP, a sentencing court must consider the individual child's circumstances, including:

The juvenile's "chronological age and its hallmark features": immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences.

The family and home environment.

The circumstances of the homicide offense, including the extent of the juvenile's participation.

The possibility of rehabilitation.

The Takeaway: Miller made the sentencing process for juveniles more individualized. A one-size-fits-all mandatory sentence for a child is unconstitutional.

The Issue: Whether sentencing a 14-year-old convicted of homicide to a mandatory sentence of life without parole violates the Eighth Amendment.

The Holding: Yes. The Court did not ban JLWOP outright, but it banned mandatory JLWOP sentences. The ruling requires that before imposing JLWOP, a sentencing court must consider the individual child's circumstances, including:

The juvenile's "chronological age and its hallmark features": immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences.

The family and home environment.

The circumstances of the homicide offense, including the extent of the juvenile's participation.

The possibility of rehabilitation.

The Takeaway: Miller made the sentencing process for juveniles more individualized. A one-size-fits-all mandatory sentence for a child is unconstitutional.

2. Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) - Making Miller Retroactive

The Issue: Does the Miller ruling apply to people who were already sentenced (and whose convictions were final) before the 2012 decision?

The Holding: Yes. The Court ruled that Miller announced a new "substantive rule" of constitutional law that must be applied retroactively on state collateral review. This meant that thousands of individuals who had been automatically sentenced to JLWOP under now-unconstitutional mandatory schemes became eligible for new, individualized sentencing hearings or potential parole.

The Takeaway: If you were sentenced to mandatory JLWOP before 2012, Miller applies to you, and your sentence is likely unconstitutional. You have the right to a new hearing.

The Issue: Does the Miller ruling apply to people who were already sentenced (and whose convictions were final) before the 2012 decision?

The Holding: Yes. The Court ruled that Miller announced a new "substantive rule" of constitutional law that must be applied retroactively on state collateral review. This meant that thousands of individuals who had been automatically sentenced to JLWOP under now-unconstitutional mandatory schemes became eligible for new, individualized sentencing hearings or potential parole.

The Takeaway: If you were sentenced to mandatory JLWOP before 2012, Miller applies to you, and your sentence is likely unconstitutional. You have the right to a new hearing.

3. Jones v. Mississippi (2021) - Clarifying the Requirements for Sentencing

The Issue: Does the Eighth Amendment require a sentencing judge to make a separate, explicit "finding of permanent incorrigibility" before imposing a sentence of JLWOP?

The Holding: No. The Court, with a new conservative majority, clarified that Miller only requires a sentencing court to have discretion to consider youth as a mitigating factor. The court is not required to make a specific factual finding of "irreparable corruption" before imposing JLWOP. As long as the sentence is not mandatory and the judge has the discretion to consider the defendant's youth, the Eighth Amendment is satisfied.

The Takeaway: This narrowed the practical impact of Miller. While judges must still consider a juvenile's youth, they are not forced to justify a JLWOP sentence with an explicit finding of permanent incorrigibility. This made it easier for judges to impose JLWOP in discretionary sentencing hearings.

The Issue: Does the Eighth Amendment require a sentencing judge to make a separate, explicit "finding of permanent incorrigibility" before imposing a sentence of JLWOP?

The Holding: No. The Court, with a new conservative majority, clarified that Miller only requires a sentencing court to have discretion to consider youth as a mitigating factor. The court is not required to make a specific factual finding of "irreparable corruption" before imposing JLWOP. As long as the sentence is not mandatory and the judge has the discretion to consider the defendant's youth, the Eighth Amendment is satisfied.

The Takeaway: This narrowed the practical impact of Miller. While judges must still consider a juvenile's youth, they are not forced to justify a JLWOP sentence with an explicit finding of permanent incorrigibility. This made it easier for judges to impose JLWOP in discretionary sentencing hearings.

Do These Rulings Apply to You? Understanding Retroactivity and Your Age at the Time of the Crime

This is the crucial question. Here’s a simplified flowchart:

What was your age at the time of the crime?

Under 18: The Miller/Montgomery line of cases is directly relevant to you if you received a life-without-parole sentence.

18 or Older: These specific juvenile sentencing cases do not apply. However, other challenges (see below) may be possible.

Was your LWOP sentence mandatory or discretionary?

Mandatory (You were automatically given LWOP by statute): Your sentence is very likely unconstitutional under Miller and you are entitled to relief (a re-sentencing) under Montgomery.

Discretionary (The judge had a choice of sentences and chose LWOP after a hearing): Your sentence is likely constitutional under Jones v. Mississippi, provided the judge had the opportunity to consider your youth and its attendant circumstances.

Important Note: The Supreme Court has never held that JLWOP is categorically unconstitutional. It has only banned its mandatory application. However, some states have since banned JLWOP entirely through their own state laws or court rulings.

Beyond Age: Other Potential Grounds for Challenge

The "evolving standards of decency" analysis is being applied to other categories beyond juveniles.

Severe Mental Illness: There is a growing movement, including dissents and concurrences from Supreme Court Justices, to extend the reasoning of Atkins (intellectual disability) and Miller (juveniles) to individuals with severe mental illness. The argument is that their culpability may be similarly diminished, and they may be less responsive to traditional penological justifications like retribution. This is not yet a constitutional rule, but it is a powerful and emerging area of litigation.

Intellectual Disability: As established in Atkins v. Virginia (2002), it is unconstitutional to execute a person with intellectual disability. Courts are now grappling with whether a categorical ban on Life Without Parole for the intellectually disabled should also exist, using similar logic about reduced culpability.

Proportionality: This is a broader, case-by-case argument. It argues that a sentence of life without parole (or a de facto life sentence) is "grossly disproportionate" to the crime committed. This is a very difficult argument to win, but it has succeeded in extreme cases, such as a non-homicide crime (Graham v. Florida, 2010, which banned JLWOP for non-homicide offenses) or a minor role in a felony that resulted in a death.

Conclusion

The landscape of the Eighth Amendment is constantly shifting. The rulings you highlighted have fundamentally changed the law for juveniles sentenced to die in prison. If you or someone you know is in this situation, the key questions are about age at the time of the crime and the nature of the sentencing process.

This information is for educational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. If you believe your sentence may be affected by these rulings, you must consult with a qualified attorney who specializes in post-conviction relief or criminal appeals.

They can analyze the specific facts of your case and the laws of your jurisdiction to determine the best path forward.

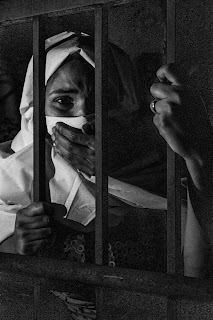

This insightful article from the Constitution Center delves into the "cruel and unusual punishments" clause of the Eighth Amendment. It traces the clause's evolution, explaining how Supreme Court interpretations have shifted from focusing on barbaric methods to assessing sentencing proportionality. The piece highlights key rulings that limit extreme sentences for juveniles and the intellectually disabled, demonstrating how the amendment's meaning continues to change with society's standards. It's a crucial read for understanding how the Constitution protects against excessive punishment.

Sign the petition here:

Comments

Post a Comment